WORDS: Phil West PHOTOGRAPHY: Honda

Born at the height of the popularity of the Paris-Dakar Rally in 1988, the first production Africa Twin was effectively an ‘off-road RC30’. Like the RC, the XRV650 was built by HRC and conceived as a no-compromise, road-going replica of a race-winner – in this case the factory NXR750 V-twin which, in 1986, won the Dakar first time out and went on to notch four successive victories.

The resultant machine, the XRV650 RD-03 Africa Twin (to give it its full moniker), was launched on May 20th 1988, caused a sensation and went on to spawn a succession of derivatives that remained on sale for the next 15 years. This is their story…

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

Born from a winner

It’s easy to forget how big a deal the Paris-Dakar Rally was in the 1980s. With the modern event now consigned to remote South America and 450 singles, the Dakar’s heyday 30 years ago was a global sensation contested by ever-more radical, road bike-derived machinery.

Launched in 1979 by Frenchman Thierry Sabine, the P-D (or Oasis Rally, as the first event was called) quickly became known as ‘The world’s toughest motor race’. Bikes, cars (and later trucks) would depart Paris on Christmas Day and over the following three weeks cover upwards of 10,000 miles across the deserts of North Africa before finishing in Dakar, Senegal. Due to its grueling nature, most participants failed to finish. Some failed ever to return home…

As a result of this extreme nature, not to mention the event’s spectacular action and scenery, the P-D quickly became hugely popular, particularly in France, where it rivalled GPs and the Le Mans 24-hour for television audiences.

This in turn led to increasing manufacturer and commercial involvement. From the outset, France’s Yamaha importer Sonauto entered a Dakar team aboard modified XT500s – the biggest and best production trail bike of the time – and Yamaha was rewarded with a 1-2 in 1979, and first through fourth the following year, both won by Cyril Neveu.

That success (Yamaha sold over 60,000 XTs in Europe between 1975 and 1985, 20,000 in France alone) attracted other manufacturers. Honda made its first official entry in 1981 (a modified XR500R single ridden by Alain Padou coming sixth) while an even more significant entry from Germany changed the template for Dakar bikes forever.

BMW had just launched its first R80G/S and, seeing the Dakar as an ideal promotional tool for its new machine, entered a team backed by its French importer. The 800cc BMW’s power was superior to the Japanese 500s and, despite the G/S’s extra weight, its flat-twin layout had a lower centre of gravity – also an advantage. BMW team leader Hubert Auriol won first time out, ahead of two Yamaha XTs, with teammate ‘Fenouil’ fourth. And although the BMWs struck problems the following year (allowing the factory Honda, this time with Cyril Neveu on board, to claim its first victory) a new era had clearly begun. Auriol, this time aboard a 980cc version of the BMW GS, won again in 1983. While his new teammate, Belgian Gaston Rahier, and despite ever-larger Japanese single-cylinder competition, won in 1984 and 1985.

It was Honda’s, and later, Yamaha’s, response to this BMW dominance that directly led to the creation of not just the Africa Twin but the whole genre of road-going ‘Paris-Dakar Replicas’ which became such a significant motorcycling genre in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

Realising that its existing singles had no hope against the BMW twins (or, later, the first Cagiva V-twin which Auriol debuted in 1985), Honda, at the request of its French importer, set up an official HRC (Honda Racing Corporation) project team in the autumn of 1984 with the aim of ‘winning the 8th rally in 1986’. Thus began the development of Honda’s first purpose-built Paris-Dakar machine. The Africa Twin’s seed had been sown.

Building for extremes

The project team, comprising Honda’s best and brightest talents in road, motocross, endurance and dirt track, attended the next Paris-Dakar in early 1985 on a fact-finding mission. It’s fair to say it was a baptism of fire.

With temperatures ranging from below zero at night to over 50°C, terrain comprising desert sand, barren rocks, gravel and even Tarmac – and the longest stages over 500 miles – none of them had ever witnessed anything quite like it before. Even so, it was enough for them to be able to come up with a list of requirements for their new machine.

It was decided the new bike should be:

- Light and compact

- Capable of 180kph/112mph with a cruising speed of 150kph/95mph

- As undemanding to ride as possible

- Reliable

- Easy to work on

- Stable at speed

- Fuel efficient (a target of 450km/280miles per tank was set)

- Have as low a CofG as possible

With all the above in mind, the first decision was to use a V-twin engine with a 45° cylinder angle and 90° crankshaft to minimize vibration – important to ease rider fatigue. In addition, this type of layout was as slim as a single cylinder, important for off-road ability. With a bore and stroke of 83 x 72mm, displacement of the liquid-cooled unit was 779.1cc producing 70bhp at 7000rpm.

To enable the range required and yet keep the CofG low a giant, saddle-type fuel tank extended down each side of the engine with a further fuel tank doubling as the ‘bash plate’ below the motor.

However, much of the rest of the bike was fairly conventional, the aim being to maximize reliability. The frame was a familiar tubular steel cradle with long-stroke telescopic forks at the front and a Pro-Link monoshock at the rear.

Finally, the resulting bike was given the name NXR and entered into the 1986 Dakar. It was to be a significant year. Suddenly the leading desert racers were all large capacity twins – or more. The factory BMW GSs were now 1040cc, the Cagiva Elefant V-twins were entering their second Dakar while fierce Honda rivals Yamaha entered – alongside its conventional XT600 singles – a radical FZ750-based four-cylinder machine.

But although not as powerful as some, it was the new Honda NXR which proved the best – enough, in fact, not just for team leader Neveu to claim victory, but for teammate Gilles Lalay to grab second. It was this success that was the catalyst for the first road-going Africa Twin.

A more aggressive Transalp

In truth, even before the NXR’s first victory, Honda had responded to the growing popularity of adventure style machines by producing new multi-cylinder production bikes.

The first, the XLV750R, an air-cooled, 750cc shaft-drive V-twin, had gone on sale as early as 1983, but despite its high tech, box-section aluminum frame, was plagued by reliability issues and wasn’t a success.

Then, in 1987, came the debut of the XL600V Transalp, another V-twin, but this time with the liquid-cooled, chain-drive engine derived from that of Honda’s 600 Shadow custom and a machine who’s concept was for fairly leisurely “long holiday rides from town over the Alps to the Mediterranean.”

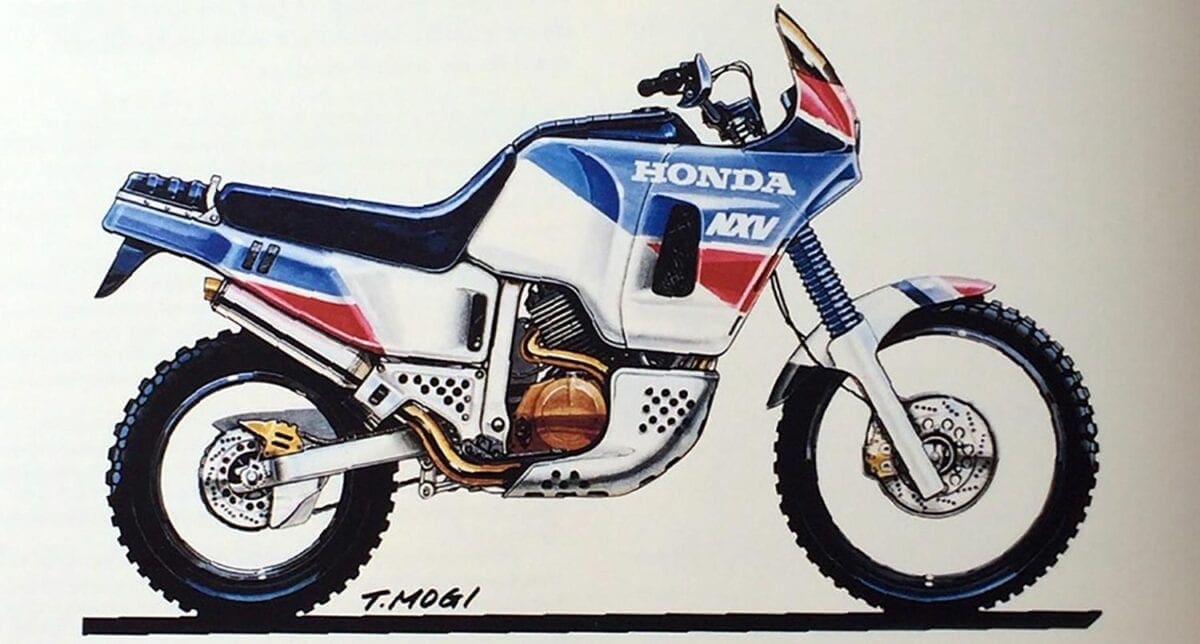

In the wake of the NXR’s success, and despite the Transalp’s popularity, Honda wanted more. Spurred on further by requests from Europe, Honda decided to produce a bike with an even more aggressive approach. Tomonon Mogi was put in charge of the project.

“At the time Honda was aiming to expand its market share in the growing Adventure Touring segment which had become extremely popular in Europe,” Mogi said years later. “Our single cylinder models stacked up well against rivals yet couldn’t quite take the lead. Then the XLV750R debuted in the Europe. This was designed by a Honda R&D group that was mostly involved with on-road models. With its V-twin engine, shaft drive and excessive unprung weight it had a lot of weak points, and was quite heavy, so nobody could really consider it to be viable in the dirt.”

In its place, he said, the idea for the new bike was to be a more aggressive and adventurous version of the Transalp; “The Transalp’s image was of a bike crossing the Alps on the way to the Mediterranean,” said Mogi. “But European dealers told us they wanted a machine that conveyed a more powerful image – of crossing the Mediterranean and charging across the Sahara desert. That was at exactly the time that the factory-built NXR had just won the Paris-Dakar. What was clear was that we would be making a replica of the NXR – it was the whole point.”

Mogi’s team started with the Transalp’s 583cc, three-valve, SOHC V-twin engine and over-bored it by 4mm to boost capacity to 647cc and raise peak power by 2bhp. After that, the plan was to make the new bike more aggressive and replicate as many NXR elements as possible.

“I wanted to make it aggressive, you see. This was going to be ridden off-road, right? So the suspension stroke had to be long. So we set the seat height at 890mm (the Transalp’s was 860mm) to give us the suspension stroke needed for off-road riding.”

Joining all that together was a new perimeter-style frame fashioned from rectangular section steel tubes and designed to be 20% more rigid – essential for high speed stability – than that of the Transalp. New, long travel, 43mm forks were derived from those used in Honda’s motocrossers, as was the box-section aluminum swing arm. The rear monoshock was adjustable not just for preload but for compression damping as well.

Cooling-wise, the newcomer had not one, but two small aluminium radiators squeezed under the tank each side of the frame, while the determination to build a true ‘NXR replica’ prompted Mogi to borrow the actual Dakar-winning bike from HRC for inspiration. He says it transformed the design process.

“On parking it at our work site we found that it exuded the true aura of the racer that had survived Africa and outrun everyone else in the desert,” he said. “It gave a really muscular impression and powerful sense of surviving in the wilderness.”

Replicating that, however, caused its own problems. Attempts to recreate the ‘suede-textured’, buckskin NXR seat forced Mogi’s team to search for a new supplier that could offer vinyl that mimicked the racer’s texture and blue colour. “It had to have the same colour as the factory-built machine.”

The big ‘saddle’ tank, meanwhile brought further headaches. As its sides extended lower than the carburetors, it required the addition of a fuel pump. What’s more, the sheer complexity of its shape necessitated new production techniques (previously all Honda tanks had been fabricated out of three pieces of steel – the Africa Twin’s required four). While the sheer size of the tank barely fitted into Honda’s fuel tank production facility in Hamamatsu.

But the quest for classy, NXR-replica perfection didn’t end there; “Another example was the quick-release fasteners used to assemble the side body panels,” said Mogi. “These were quite expensive. We were told they were prohibitive, cost-wise, but the NXR used those fasteners so we insisted that the Africa Twin had to have the same.”

Then there was the headlamp cover. “The NXR’s headlights had a steel mesh stone guard attached,” said Mogi. “So we wanted to include this as well to convey to the user the same feeling at the Dakar racer.”

In fact, everywhere you looked, the emphasis was on making the new bike appear every inch the factory-built racer. That’s why the newcomer got a fully stainless steel exhaust. That’s why it had an ‘auxiliary type’ instrument panel (where the panel is made up of different, separate elements). And that’s why, when it finally went into production, it was built at HRC as well. The HRC ‘tricolore’ colourscheme went without question.

And the name? “Africa Twin was decided upon based on the comments of one of the European sales staff who said ‘It must be a real Africa Twin if it has the V-twin engine that raced through Africa.’” A legend was born.

That first Africa Twin was launched on May 20th 1988 and proved an immediate sensation (even though it was never officially imported into the UK). Two years later, however, Honda produced a successor – the XRV750, or RD04, which did make it to the UK and remains highly prized today.

Although undeniably the better bike in numerous respects (improved engine performance and braking power being the most obvious), the 750 was also clearly built to a lower standard than the original 650. Production was no longer by HRC, build quality and fit and finish was clearly not to the same standard and its specification didn’t match the heights of before, either. For example, the fasteners and ‘suede’ seat-top Mogi had fought so hard for with the original were no more. No longer was the Africa Twin a pure NXR replica.

Three years after that, even more significant changes were made. With 1993’s new XRV750 RD07, it wasn’t the engine, but the chassis and bodywork that received a makeover with a new frame, repositioned and lower fuel tank, a lower seat (both to improve handling) and all-new bodywork.

In this final incarnation (there was a final slight update in 1996 which saw a revised cowling and higher screen) the Twin lived on until 2003, co-existing for its final four years alongside Honda’s new, more powerful, but larger and less aggressive XL1000V Varadero. Finally outgunned by newer, bigger rivals, the Africa Twin was at last deleted. Today, however, all retain a strong, devoted following, thanks to their durability, style and versatility, while the original RD03 650 is at last becoming an appreciating modern classic. Modern adventure bikes simply wouldn’t be what they are today without it.

Tomonori Mogi

Unusually for Japanese designers and engineers, Mogi started at rival Kawasaki and spent 12 years in its motorcycle division working on bikes such as the Z1300. Born in 1952, he joined Honda 30 years later where he was involved in the design of the XR80/100, Dominator, Africa Twin and GL1800 Gold Wing before transferring to Honda’s Brazilian division in 2002.

“In creating the Transalp, the single-cylinder Dominator and then the Africa Twin, we succeeded in putting bikes with three distinctive styles on the European ‘Adventure Sports’ market, just as we planned. We created these machines while keeping in mind that what our users wanted was what we wanted. I think we clearly conveyed that idea to others. The Africa Twin definitely filled the role it was created for as an on/off road racer replica.”

1988-1989 XRV650 Africa Twin (RD03)

Engine: 647cc liquid-cooled 52° V-twin

- Bore x stroke: 79 x 66mm

- Power: 57bhp (43kW) @ 8000rpm

Suspension: (F) 43mm Showa fork, 230mm travel; (R) Pro-Link monoshock, 210mm travel

- Brakes: (F) Single 296mm disc; (R) 210mm disc

- Seat height: 880mm

- Dry weight: 185kg

Fuel capacity: 25 litres

1990-1992 XRV750L-N Africa Twin (RD04)

Engine: 742cc liquid-cooled 52° V-twin

- Bore x stroke: 81 x 72mm

- Maximum power: 62bhp (46kW) @ 7500rpm

Suspension: (F) 43mm Showa fork, 220mm travel; (R) Pro-Link monoshock, 214mm travel

- Brakes: (F) Twin 276mm discs; (R) 256mm

- Seat height: 880mm

- Dry weight: 185kg

Fuel capacity: 23 litres

Notes: Second Africa Twin had a new V-twin engine, extra front disc (and larger rear) and revised bodywork.

1993-1995 XRV750P-S Africa Twin (RD07)

Engine: 742cc liquid-cooled 52° V-twin

- Bore x stroke: 81 x 72mm

- Maximum power: 62bhp (46kW) @ 7500rpm

Suspension: (F) 43mm Showa fork, 220mm travel; (R) Pro-Link monoshock, 214mm travel

- Brakes: (F) Twin 276mm discs; (R) 256mm disc

- Seat height: 860mm

- Dry weight: 207kg

Fuel capacity: 23 litres

Notes: Updated model with revised chassis, repositioned (lower) fuel tank, lower seat and all-new bodywork.

1996-2003 XRV750T Africa Twin (RD07A)

Engine: 742cc liquid-cooled 52° V-twin

- Bore x stroke: 81 x 72mm

- Maximum power: 62bhp (46kW) @ 7500rpm

Suspension: (F) 43mm Showa fork, 220mm travel; (R) Pro-Link monoshock, 214mm travel

- Brakes: (Front) 276mm discs front; (R) 256mm disc rear

- Seat height: 860mm

- Dry weight: 207kg

Fuel capacity: 23 litres

Notes: Slight update with revised fairing, new headlight surround and higher cowl for more protection. The seat was reshaped for extra comfort.

1986-1989 HONDA NXR750

The inspiration for the Africa Twin, the NXR was a purpose-built racing machine developed and built by Honda’s racing division, HRC (Honda Racing Corporation).

It won the event on its debut in 1986, and went on to record four consecutive victories before Honda officially withdrew from the event in 1989.

Powered by a compact 45° V-twin producing 75bhp, its key strengths were excellent handling – even when fully loaded with 59 litres of fuel – and high-speed stability.

The NXR’s four consecutive victories were a record only matched by Peugeot in the car category and was unrivalled until Yamaha also claimed four consecutive victories from 1995 to 1998.

Honda NXR750 Paris-Dakar roll of honour

- 1986: 1st Cyril Neveu, 2nd Gilles Lalay

- 1987: 1st Cyril Neveu, 2nd Edi Orioli

- 1988: 1st Edi Orioli, 3rd Gilles Lalay

1989: 1st Gilles Lalay, 3rd Marc Morales

SPECIFICATION

Engine: 780cc liquid-cooled 8v 45° V-twin

- Bore x stroke: 83 x 72mm

- Maximum power: 72bhp (54kW) @ 7000rpm

- Seat height: 990mm

- Dry weight: 125kg

Fuel capacity: 59 litres

Honda XRV650 Africa Twin ‘Marathon’

If the standard 650 Africa Twin wasn’t exotic enough, for a brief period Honda built another, limited edition version, specifically for desert racers – the XRV650 Africa Twin ‘Marathon’.

In the late ’80s, with the growing involvement of ever more exotic, factory-built prototypes, a second motorcycle category was created for production-derived bikes – the ‘Marathon class’ – and it was to be arguably the Africa Twin’s finest moment.

After three successive victories with the NXR750, a planned withdrawl of the official Honda team after the 1989 race and the recent launch of the production XRV650 Africa Twin, Honda France director Jean Louis Guillot announced a programme to support 50 Africa Twin riders in the 1989 Marathon category of the Paris-Dakar.

In due course, 50 riders were selected from 150 applicants, each allocated specially-prepared Africa Twins – the Africa Twin ‘Marathon’. The key upgrades to the bikes were bigger fuel tanks, a water tank (for the rider) and uprated suspension, tyres and exhaust.

49 of these made it to the start line (the 50th, a French serviceman, was denied entry into Libya a few days earlier), 18 made it to the finish and Patrice Toussaint and Patrick Sirevjol came first and second in the class. Honda France repeated the project the following year, grabbing first and second again. Today, these are the most desirable of all Africa Twins.

Motorcycle Sport & Leisure magazine is the original and best bike mag. Established in 1962, you can pick up a copy in all good newsagents & supermarkets, or online…

[su_button url=”http://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/issue/MSL” target=”blank” style=”glass”]Buy a digital or print edition[/su_button] [su_button url=”http://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/subscription/MSL/motorcycle-sport-leisure” target=”blank” style=”glass” background=”#ef362d”]Subscribe to MSL[/su_button]